It’s been reported that sales of George Orwell’s 1984 skyrocketed the day after Kellyanne Conway’s instantly infamous “alternative facts” blunder. So the cloud of lies, acrimony, ignorance, and intolerance that was this week may have a silver lining. I hope as many people get a chance to read Orwell’s masterpiece as possible.

But I fear that if they’re simply looking for allegory (in the mode of what I call correspondence similarity), they’ll be missing out on what makes the book a masterpiece in the first place. If you simply want some insight on the authoritarian mindset and the ease with which a populace can go from civil and critical to cruel and cretinous, I’d point you to Orwell’s essays and memoirs. And anyway, Trump is really more of a Berkshire boar (Napoleon, Animal Farm) than a Big Brother. 1984, I submit, is a novel about beauty.

The twentieth century was full of fiction writers who regretted the intensity with which their readers saw allegory in their works. J.R.R. Tolkien and David Foster Wallace spring immediately to mind. As far as I know, Orwell didn’t have much to say about this (although he was already dying as he finished 1984), so I’d like to make the argument for him.

There’s no doubt that 1945’s Animal Farm should be read as allegory. Its subtitle is “A Fairy Story,” and fairy tales are didactic by nature. As for 1984, there’s no denying that it sprung from a very particular historical moment, when Stalinism was rapidly filling the vacuum left by the annihilation of Hitlerism. Orwell took a bullet in the neck fighting fascism in Spain, but he focused more of his intellectual energy battling Stalin and his acolytes in the West. Willfully ignorant of his pro-socialist writings, conservatives today take Orwell’s anti-Stalinism as a sign that he was one of theirs. Shudder. As a pathological contrarian, but also as a man of the Left, Orwell’s later writings were aimed at his fellow travelers more than anyone else. Look all the way back to The Road to Wigan Pier, and you’ll see how little comfort Orwell ever had to offer for those with whom he had political sympathies. And I have no doubt that 1984 did begin with that line of thinking.

Despite the recent deaths of his wife and sister, along with early signs of the TB that would claim his own life, Orwell’s last years on Jura may have been some of his best. I suspect that amid the desolate charm of the Hebrides and in the comfort of his new wife and son, Orwell thought a lot about beauty and love as 1984 took shape. The novel, which, again, probably did begin as a dystopian allegory, became an enduring work of capital “L” Literature.

When confronted with the cynicism of Trump and his soulless corps of professional liars, we’re easily reminded of “doublethink” and “2+2=5.” But please bear in mind that Winston Smith’s notion of truth was never just about the absence of falsehood. The world has already surrendered to cynicism when truth is reduced to a negative quantity. Winston’s truth is more like the implacable Good at the base of all forms in Plato’s thinking. If we see truth as the absence of falsehood, and the opposite of falsehood as mere fact, then the ending of 1984 is grim indeed. And looking back from its ending, the entire novel might present the kind of pessimistic vision we’d come to expect from the earlier Orwell. Winston, having seen all of the facts laid out in Goldstein’s pamphlet, is taught to refuse those very facts by O’Brien, the operative who gave Winston the pamphlet in the first place. And after Winston’s mind is finally “perfected,” he will be shot in the brain. (BTW, if you want to glean some real world correspondence from the novel, Goldstein’s pamphlet is an amazingly prescient indictment of the military-industrial complex that eventually bankrupted the Soviet Union and which bears a lot of responsibility for the sorry state in which the U.S. finds itself today).

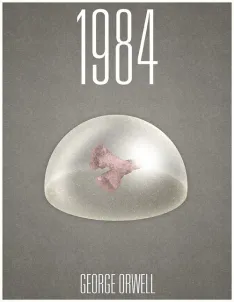

But the facts that O’Brien supplied merely provided extensions to what Winston already knew. The truth had already been revealed to Winston the moment he picked up the pink coral paperweight at Charrington’s shop. The look, feel, heft, and–above all–the uselessness of the object made it precious and beautiful to Winston. The paperweight was not only a link to the past–a reality outside of the Party’s ceaseless present–but an element of eternal creation. To say that the paperweight is a tangible reminder of a better world that had been and could be, however, does not do it justice. To reduce the object to its tangibility (to its extension in space) is to reduce it to a fact in the world, no different than the words in Goldstein’s pamphlet. Remember, facts did not save Winston in the end. The paperweight was an object beyond fact, a thing with its own affective powers. What Winston experienced when he picked up the paperweight was an aesthetic moment, an instance of pure creation, and an affirmation of what John Berger called “man’s ontological right” in the world. Here, ontological right is not about power or dominion, but about freedom from alienation, the kind of which we experience in moments of creation–if we allow ourselves that right. That’s truth. That’s truth that asserts itself over and over again in little moments of beauty and in uncelebrated acts of love.The ontological right is asserted again in Winston’s love affair with Julia, and again as they stand together at the window listening to the prole washerwoman’s song.

The paperweight was planted by Charrington (revealed as an agent of the Party). Winston and Julia’s lovemaking was recorded and recycled for prole consumption. The washerwoman’s song was manufactured by a machine. Winston and Julia betray one another. Winston will be shot in the head. The surveillance, the propaganda, the doublethink, the psychological and physical torture–all of it, as O’Brien calmly explained, was to no other end but power. But truth, which is repeated in those moments of beauty and love, which are in turn acts of irreducible creation (irreducible to means and ends), is the failure of power. Those acts in those moments cannot unexist. Creations can be destroyed, but the creating cannot. Turning Winston against Julia and himself before shooting him was not a victory for the Party, but the limit of its power. The beginning of its end.

I like to think Orwell trusted his readers enough to see this.